My friend and colleague Ian McDonald tweeted that our local library is in danger of being privatised.

Pros and cons of this decision aside, the article says:

The authority said it has completed a public consultation that assessed how to “provide better value for money but also encourage people to use our libraries more”.

It has seen a drop in the number of visitors aged between 16 and 44.

As a member of the public firmly between the ages of 16 and 44 (near-on exactly between, as it turns out), I'll offer an opinion.

I like books, though I don't particularly care to own them; I am not particularly attached to books physically (they don't smell as nice as they did when I was a kid), and I'll rarely re-read a book soon after the first time through. Further, I've lived in three countries in the past 5 years; books tend to be heavy and more expensive to cart around than just to re-buy in a new country.

You might think I'm a perfect candidate for a Kindle, and you would probably be right, if not for two reasons:

- I like the lendability of books, which Kindle is only starting to address

- E-books aren't nearly cheap enough

A good public library addresses this situation.

A good public library

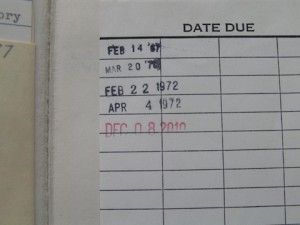

Before moving to Richmond, we lived in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada for two years. Though their libraries were physically as much a living relic of the 1970s as any other, and their website was more Web 0.5, the Kitchener Public Library and I had a beautiful thing going. It worked a little like this:

- Go to a book store

- Look in sections of interest, and on the "What's New" table

- Write down titles

- Go to KPL website and reserve books

Cost to me: $0. Time expenditure: minimal. I would then get an e-mail when the books I wanted were available; I'd walk into the library (conveniently, not even 5 mins from my work), go straight to the reservation shelf, walk the book the ten steps to the counter, and be out in under a minute.

I generally go to bookshops as time-wasters while in shopping malls. When I'm in a bookstore, I already have a book I'm reading at home. I am not there because I have nothing to read; I'm there because I want to know what I might want to read one day. The somewhat random nature of library reservations worked well for me, in that I would get books as they came available. If I ended up with more than I could read at once, I'd just re-reserve the ones I didn't have time for. Remember, this is just me; I know that your mileage will almost certainly vary.

A not-so-good public library

How does this work in Richmond?

- The Richmond library network probably doesn't have the book

- If they do, you pay almost a pound per book for reservation (average price of a paperback book: £8?)

- There are so few copies of books, spread amongst many branches, that it can take months to get to you if it's half-way popular

- To top it off, most commuters probably get back to Richmond after 6pm, when the library closes.

See why I don't bother going to the library?

Why libraries are hard

Lets ignore all the other benefits of a library as a civic space (as I rarely use them myself, so on the theme of privatisation, I wouldn't pay to keep them around) and focus only on the borrowing.

Generally, my discovery system tends towards the popular books - those that make it into Whitcoulls/Chapters/Waterstones etc - though there are some that I learn about online and would love to read. To me, libraries have always felt like they are places where books go to die. In some cases, libraries are probably the only place to find old books; it should be pointed out that fiction rarely changes, but non-fiction books are often supplanted, or refer to outdated concepts.1

This sounds like a problem that requires consideration of the "long tail" theory. Consider, for a second, Amazon.com. They already have a warehouse system, allowing them to stock goods that likely wouldn't be profitable to show in a store. For anything more than that, Amazon opened their platform to let others advertise on it: the additional cost of listing rare items tends towards zero. Other people can make a business of selling rare books, perhaps at a higher cost, or perhaps just for the love of rare books. Maybe the stock isn't kept on hand, and has to be ordered from the publisher as each copy is ordered. Maybe, over time, this model will tend towards businesses like Lulu.com, where, when you order a copy of the book, it will be printed for you there and then. Imagine that in your library?

So, as time passes, the 20% moves into the 80%, and the popular books move into the long tail. Libraries obviously keep books a long time. Why show them? Have the most popular books - the 20% - on display, and the rest discoverable online, where the council suggests most people are already looking.2 The library of my teens, the Hamilton Public Library, had a section called "Core Stock" which contained a lot of their older books; however, it was still a (relatively small) room you could go walk around. Make this a machine-indexed basement, and charge people for getting books that they can't get any other way - a rare book is worth far more than 80p to someone who wants to read or cite it.

Why not offer a Netflix model, where I can pay ~£4 for a book which is posted to me, and comes with a return envelope?

The council knows that 16-44 year olds use the Internet, and know what they want. The job of letting people know what books exist no longer needs to be performed by a library. Many enjoy browsing shelves looking for a book, so keep a browseable library,3 but a much more focused one; then optimize the case where people want to order a book online and have it get to them somehow.

I'm not sure Richmond council can wait on the existence of miniature publishing machines (and the requisite copyright changes) to make a decision on their library. A public library has to compete with other media (film, internet), free (pirated books), digital/electronic and easy (Kindle, iBooks etc), digital/paper and easy (Amazon). In a business context, many people try and compete by charging more and offering a better service; not really something that local government can do. I'm sure it can find a niche. If it can offer a good solution to my workflow, as Kitchener did, great. Maybe the time will come for libraries to stop existing altogether, but I don't think we're there yet.

- As much as it would be a walk down memory lane to re-read the Commodore 64 books I read when I was 8, I don't think they need to be taking up space on library shelves. ↩

- And make the online display appealing - you have all the space, and attention, you want. Show full cover images, rather than thumbnails, and link to web services that can tell you more about the book from its ISBN. ↩

- Or build your branches next to a book store. That'll learn 'em! ↩

Subscribe with a news reader (RSS)

Subscribe with a news reader (RSS) Have new updates sent by e-mail

Have new updates sent by e-mail